| January 1 - 31, 2014 | Online |

Visual AIDS and The Body

present:

some thoughts / for you

Dedicated to the Members of Viausl AIDS

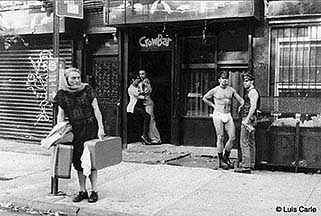

LUIS CARTE

"Crowbar, NYC", 1996, Gelatin silver print, 8" x 10"NOTE: Previous exhibitions are also available on the website.

i.

The thematic thread of this gallery lies in the detailed representations of spaces in these artworks: rooms, domestic spaces, interiors, streetscapes, city landmarks, public places, the out-of-doors. While we tend to look primarily at the human subject(s) in these artworks, the spaces depicted are nevertheless important components to each photograph and painting, full of information and meaning.

Spatiality and environments are something I’ve started to always look for when I engage with the visual archive of HIV and AIDS. They speak to how people lived and live, to everyday lives and experiences, to resistance and challenges.

These representations of spaces resonate with me strongly.

ii.

Particularly, I look for traces of these spaces in art in the hopes that they can provide an expanded sense of the spaces we get to be in presently. I’ve been thinking a lot about something the artist and writer Avram Finkelstein said when my friend Alex and I interviewed him earlier this year. We were talking about memorials and PTSD and his community of AIDS survivors, and he said “there’s this complete lack of place for us to be,” and those words keep echoing in the chambers of my mind.

iii.

I think it is an activist act—a creative and a critical act—to try to envision what this “place” could look like, and to work towards it. I somehow doubt that the solutions lie in a state-sanctioned memorial site, though I could be wrong. In my imagination, it takes on a variety of forms, including actual physical spaces, relationships between people and communities, really good access to support and services for everyone; a sort of overarching system and network of healing and wellbeing, all founded on land justice, the ending of oppression.

iv.

When Visual AIDS asked me to curate January’s web gallery, I first thought about the sorts of images I wanted to explore (mostly New York City-based; mostly photography, for its ties to documentation, with some exceptions; and most importantly, they had to depict space in some way). I then spent a few days slowly pouring through the archives, bookmarking images that stood out somehow. The process of curating this gallery was a largely intuitive one, based more in aesthetics and visuals than historical research and facts. I did not have time to find out the backstories of every image in this collection (as a formally trained art historian, this troubles me somewhat, eats away at my professional instincts. Nevertheless..).

v.

I see some of the visual essence of these images reproduced in the world around me. Lately, this aesthetic afterlife plays out, at times, in the fashion choices made by the gay boys in the neighborhood I live in—my friends—their subtle updates on the sneakers and jeans and baseball caps and glasses-frames stylings adopted by their predecessors. The problem for us is, a lot of our predecessors are missing, gone; they’re dead. Our generation of queers grapples with this massive loss that occurred just as we were coming into the world, and this it is a hard thing to know what to make of. We know we’ve lost an entire generation of people who would have been or were our queer parents, uncles, aunts. How to engage with this loss, how to understand the ripples of its after-effects? This is partly why I like looking at art from this period, and learning about its particular contexts—I understand it as a way to connect with those who are gone, to engage with our shared humanity.

vi.

The power in these depictions of space by poz artists is that they are creating these representations, driving them. In New York City, space is subject to the ever-tightening grip of capitalization: New York has become a nightmare of gentrification. In the United States and Canada, we walk for the most part on unceded indigenous territory. We live in a world where land justice is severely lacking, here and in other places, demonstrating the need for a tangible shift in how we think about place and how ew make space. And we live in a time where the prison industrial complex is actively constituting the body of the positive individual as a criminal one, imposing . In this regard, our spaces are so important—clearly threatening enough to the state industrial complex that they seek to sequester these very bodies into jails. Let’s start making those connections more tangible, more viable, more direct. Thinking about the links between HIV and AIDS and other social movements, resistances, losses, histories. And enacting these queer spaces in resistance to the gentrifying and colonialist forces we struggle against today.

vii.

I think that it’s really important to look at the details of the artwork in the Visual AIDS archive. One thing I love about looking at the spaces of these images is the second-hand information it yields about the people occupying them, almost as if revealing secrets; aesthetic afterthoughts brought to the fore once more. Ian and Vincent recently did a wonderful job of critiquing the decontextualization of the aesthetics of our struggle [LINK]. I have a sneaking suspicion that these visual details can be experienced as sites of visual resistance: capitalism, in relation to the HIV and AIDS archive, is too preoccupied with subsuming and mainstreaming the big and bold visuals, and with making a profit, to give much attention to the details. Our details. And fortunately for those of us resisting the capitalization of this history—and there are, hearteningly, so many of us—there is an abundance of details in this visual archive which serve, in their own ways, a multitude of functions: details to pause on to remember, or reflect, to mourn, to draw inspiration from, to transform ourselves, really.

When I look at the spatial aspects of these images, I’m reminded that poz people have continuously made space and shaped space for themselves in complicated, empowered and creative ways. Being able to visualize, within the archive, these historically queer spaces is no small, unsignificant thing. For me, it makes the archive a place of hope.

viii.

I can identify an ongoing sense of longing within myself, that I think so many of us share, for some sort of space or place where wrongs have been righted, where people feel good and can be themselves and where they are free. I like walking around this giant city today with the sense that there are places, dotted throughout, that are imbued with historic significance and with community memory. I think that memory can never be taken away, and that is a powerful thing. And when you know about what happened in a specific place in the city, for instance, your relationship to that place is transformed. I believe that New York City is full of these “places”. Could this offer some clue, some key to solving the troubling “lack of place to be” that Avram speaks of?

ix.

The afterlife of images is a strange and wonderful thing.

Many of the images I chose here have stayed with me in strange ways, haunted me somewhat. Surprising images, too, ones I didn’t expect. Funny details in the images that come back to me in unexpected moments, interrupting my quotidian routine, making me think differently. It is my hope that they will stay with you, the reader/looker, as well.

Visual

AIDS

526 W. 26th St. # 510, New York, NY 10001

Phone: 212.627.9855

· Fax: 212.627.9815

e-mail: info@visualAIDS.org

Visual AIDS Gallery